by Beatrice Ricci

City Space Architecture

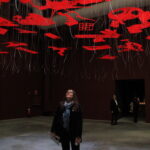

On 20 May 2023, the 18th International Architecture Exhibition opened to the public in Venice. This exhibition, also known as the Venice Architecture Biennale, is one of the most important international architecture exhibitions, bringing together the work of practitioners and theorists from all over the world. Founded in 1980, each edition has its own curator and theme.

This year’s Architecture Venice Biennale is entitled “The Laboratory of the Future” and is curated by Leslie Lokko, a black woman who has dedicated her career to studying and improving architectural studies in Africa. In fact, after directing the School of Architecture at the City College of New York, Lokko founded and directed the Graduate School of Architecture at the University of Johannesburg in South Africa. Furthermore, believing that Africa can be a valuable reference point for understanding how to address some of the world’s current problems, she founded and currently directs the African Futures Institute (AFI), an independent postgraduate school of architecture in Accra and a public events platform. The idea of Africa as a possible laboratory of the future, rather than an exploited land, is at the heart of this year’s Biennale and marks a break with previous editions.

Conceived as a laboratory for the future, the Biennale aims to create a counter-narrative in the discipline of architecture and to rethink the future of the planet in the face of the current climate crisis. Decolonisation and decarbonisation are indeed the two main themes of this year’s Biennale. The novelty of Lokko’s perspective lies in the intersectional lens through which she approaches the contemporary crisis, which intertwines class, race, gender and climate change issues.

This leads to a questioning of the idea of the ‘public’ as a community and of ‘space’ as a common ground that we must share and care for. For Lokko, the urgency of this edition of the Biennale lies precisely in redefining this shared community, which has not been properly inclusive and equal. Since the history of architecture and architectural exhibitions has always been dominated by the global North, “what is missing from the statement is any acknowledgement of who the ‘we’ in question is”. On the other hand, Lokko is aware that the Venice Biennale, as an international event that brings together people from all over the world, has its own environmental impact, and this is something we can no longer ignore. However, in Lokko’s idea of the exhibition, this issue is not just an unnecessary display of archistar offices, but a pragmatic tool to become an “agent of change” here and now. This is what makes this edition of the Biennale unique and urgent.

Lokko defines the exhibition as “a moment and a process”, focusing it on the idea of change. It proposes a pragmatic imagination of the future based on a redefinition (in the present) of architecture and the role of the architect.

This change of course is reflected in the structure that Lokko has given to this year’s Biennale. The exhibition includes 89 participants, half of whom are from Africa or the African diaspora. There is also gender parity in the representation of offices, most of which are small, emerging, young and focused on research rather than construction. As with every Biennale, the two main areas where the exhibition takes place are the Giardini and the Arsenale. The central pavilion of the Giardini houses what Lokko calls the force majeure: 16 architectural practices representing the architectural production of Africa and the African diaspora. The Arsenale hosts the dangerous liaisons section, alongside the special projects selected by Lokko. Both spaces feature works by young African and diaspora ‘practitioners’, the Guests of the Future, whose work directly confronts the two themes of the exhibition: decolonisation and decarbonisation.

As further proof of the Biennale’s ‘laboratory’ character, there is also the rich interdisciplinary supporting programme ‘Carnival’ and the first Biennale College Architettura for young students, graduates and professionals.

Within this laboratory of the future, interesting perspectives on the notion of public space will be directly or indirectly put on the table for discussion, as the following brief selection of pavilions and projects will show.

Following the idea of self-criticism of the exhibition as a shared space with an environmental impact, the work of the German Pavilion in the Giardini section fits very well. With the installation “Open for maintenance”, the curatorial team has equipped the pavilion space to make visible what is usually hidden: the making of an exhibition. The installation, which is close to a collective performance, consists of a central area where the latest waste from the Biennial is sorted and catalogued. Each piece of rubbish is provided with a QR code that brings it back to its former use, showing the original artwork or equipment. The rest of the pavilion ceases to be an exhibition space and is transformed into a construction site of working spaces such as a meeting room, a kitchen and a laboratory. The working process that precedes the Biennial, which is usually private, becomes open and shared with visitors. In this process of rethinking the future proposed by the 18th Biennial, should we also rethink the division between working spaces and living spaces? What we do in these spaces, such as care work, must be private or shared with the community on a more equal basis?

In the Arsenale section, among the guests from the future, the work of Rashid Ali (Hargeisa, Somaliland, 1978) shows us the peculiarity and diversity of problems related to the design of public spaces in areas of the South of the world. As an emblematic case study, he exhibits a scale model of the Hargeisa Courtyard Pavilion project, a pink concrete canopy that surrounds a small garden with a fountain. The idea behind this project is to create an open social space, the same public space that in the region of Somalia is usually formed by large canopies under which stories are shared. In this choice, the intention is to re-establish a link with the Somali land from which Somaliland wanted to separate politically by creating an autonomous state (not recognised by the international community). Much of the studio’s work consists of repairing the city with small, strategically placed areas – pavilions, walkways, alleys, courtyards and small squares – in response to the scarcity of land and resources.

The design of public spaces is at the heart of the work of the Italian collective Orizzontale, which is presenting its installation “Sexy Assemblage – The Danger and Seduction in the Juxtaposition of Differences that May Clash” in the Arsenale’s “Dangerous Liaisons” section. The young studio from Rome will be presenting some of its public space projects in an overlapping way, allowing for connections and new proposals that have not yet been calculated. The unpredictable relationships (between people, between places, between competences, between stories, between materials) are at the heart of their idea of public space, which they usually equip with simple and essential infrastructures.

Their installation is interesting and incisive because it is itself a public space: a coloured platform with a simple wooden table on one side and bleachers on the other. On the wall is the question “How to deal with public space?”, which seems to invite visitors to open the debate in Orizzontale’s site-specific space. Orizzontale’s work creates a break in the (sometimes overwhelming) flow of installations in the corridors of the Biennale. It reveals its effectiveness in its gentle way of creating a space to linger and talk. It seems to suggest that one possible way to face the crisis we’re experiencing is very simple and human: just sitting around a round table, looking at each other and sharing.

This idea of sharing knowledge, experience and good practice from local communities is also at the heart of the Italian Pavilion, entitled “Spaziale” and curated by the young collective Fosbury Architecture. The pavilion brings together nine projects by young offices or collectives working in Italian areas that are representative of conditions of fragility or transformation. Each intervention considers the built object as a tool and not as an end in itself, focusing on the slow and long process that the relationship with local communities implies. The interesting perspective of the Italian Pavilion is contained in the title itself. The word “spaziale” underlines the idea that the discipline of architecture must focus more and more on the relationship between people and places, leaving behind self-referential authorship and embracing the slow and long work of participatory processes with communities. This perspective confirms and renews the importance of public space as a space shared by a community, both in cities and in marginalised contexts.

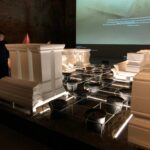

In the Arsenale section, the work of DAAR – Alessandro Petti Sandi Hilal investigates the issue of decolonisation, specifically the possibility of critical reuse and subversion of fascist colonial architecture, through an art installation that deals with public space.

The object of her research is the village of Rizza in Syracuse (Sicily), built in 1940 by the Sicilian Latifund Colonisation Authority (ECLS) with the aim of repopulating and modernising Sicily, which was considered underdeveloped. The architectural language became a symbol of an ideology that compared the small Sicilian village with the city of Asmara in Eritrea. When the latter was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2015, it was necessary to reflect on the cultural weight that fascist modernist urban planning and architecture has brought with it and how to enter into a dialogue with it: do we have to erase it or do we have to reappropriate it and give it a new meaning? This is a question shared by the coloniser and the colonised.

DAAR chooses the second way. It takes back the façade of the main building of the village of Rizza and transports it horizontally, transforming it into an artistic installation made up of mobile modules. These become seats around a table that allows for collective discussions aimed at promoting a fascist counter-culture. This installation becomes a public space, a place where different opinions and ideas react against the fascist ideology that has recently returned to Europe, as DAAR says in the video that accompanies the artistic installation (available on YouTube).

This new architecture changes from a fascist symbol to a symbol of a heterogeneous and democratic community. This installation was repeated in different places before arriving at the Venice Biennale. The unity and impact of this political action was worth the Golden Lion for the DAAR studio. Indeed, it perfectly embodies the idea of questioning the past in order to build a new future, which the 18th Venice Architecture Biennale emphasises.

Another dangerous link between past and future from a new perspective is the one made by Eyal Weizman (Haifa, Israel, 1970) and David Wengrow (UK, 1972) together with Forensic Architecture with the Nebelivka hypothesis.

New technologies have made it possible to discover 6000 year old settlements that could change the current concept of the city. These ‘new ancient’ settlements have been discovered between the southern Bug and Dnieper rivers in central Ukraine, less than a metre below agricultural fields.

They are similar in scale to the early cities of Mesopotamia, but these first Ukrainian cities lack centres. Or rather, they are organised as concentric rings of domestic buildings around a mysterious open space. There are no traces of temples, palaces, administrations, rich burials or other signs of centralised control or social stratification. This urban plan appears to be free of hierarchies and therefore redefines the urban planning systems that dominate most cities in the present day, and even the definition of what is public and what is private space.

Moreover, these ancient settlements seem to have triggered the formation of chernozems, some of the richest soils in the world. This would be the first case of “anthrosol”, soil created by humans. This calls into question the relationship with the land, which is seen as a common good to be cared for, made more vital by man, and not expropriated or exploited until its resources are exhausted.

The overarching idea that runs through all the sections of the Biennale is the need to redefine a shared ‘public’ knowledge of architecture, giving visibility to all the subjects that have been kept apart until now. There is also an urgency to rethink land ownership, with the aim of collective care of the earth, overcoming the distinction between public and private, because what people do in private space affects the whole community in terms of environmental impact.

In this moment of crisis, perhaps we have a path to follow, and it leads us to the “South” of the world, which we must use as an example, rather than simply taking advantage of it.

More Stories

Public Space Research and Design: Tracing Gender and Sexuality Inequalities

As the Space becomes Public, the Public becomes Space

Fighting sexual harassment: how to foster accessible and safe public spaces